By Ray Cleary

2 August 2022

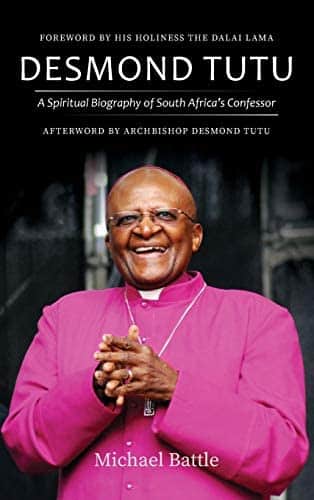

Michael Battle, Desmond Tutu A Spiritual Biography of South Africa’s Confessor (Westminster: John Knox Press)

I need to be upfront about this review. I have been an avid follower and admirer of Desmond Tutu my whole ministry and regard him as a mentor in absentia. I have had the privilege of meeting him on a few occasions, including breakfasting at Bishopscourt in Melbourne, participating with him in a service for 2000 young people from schools across the Melbourne diocese in 2000. His biographer also notes his personal relationship with Tutu.

Tutu has been described in many ways throughout his life’s ministry: a tiny giant, the little battler, an angry man, and one who uses the cloak of religion for his political agenda and ambitions. He has been both inspiring and challenging to many bishops in the Anglican communion with his views on matters of sexuality, justice, exploitation, colonialism, and his outspokenness and willingness to engage in the public forum when others remained silent. Throughout the book Tutu is described as one who speaks truth to power. This has set him apart from many church leaders including in his home church. Tutu’s own racial identity as preacher and bishop of the Anglican church dismayed some. His use of the rainbow image from Genesis inspired many to move beyond the ideology of white supremacy and instead to see the rainbow as a sign of shalom, or peace, signifying that all are created equal in God’s dream for the creation. As his biographer says Tutu believed that every person was invested with value, and not simply through “arbitrary biological attributes”.

Tutu’s world view was not confined to the Church, but to the whole of creation. His moral authority is spiritually grounded in his faith as ongoing revelation. These themes are explored in the book at some length, albeit in repetitive and wordy style at times. Many who opposed Tutu also embraced Christianity as their faith and saw his approach to apartheid and other forms of injustice as a distortion or corruption of the teachings of Jesus. Instead, they argued the Church should be above politics.

Read more: ‘Very warm’: Melburnians remember Archbishop Desmond Tutu

The writer acknowledges the challenges he faced in writing this book with his belief that the Western world does not seem to be interested in the spiritual or for that matter anything about God, particularly the Christian God, that distracts from the imperative of self-interest and power that seems to pervade many parts of the world. While Tutu embraced diversity in the Church, he also recognized the place of other faiths, demonstrated by his friendship with the Dalai Lama.

The author spends much time defining Tutu’s spiritual life through three stages of Christian mysticism, namely purgation – his formation as a leader in both church and nation; illumination – his role as confessor and reconciler; and union – his role as wise elder or sage. Central to this exploration is the concept of “Ubuntu”: the place of mutuality in forming human nature expressing fully what it means to be created in the image of God. In these sections, the writer explores Tutu’s storytelling, humour, and anxieties, as well as his relationships with Nelson Mandela and political leaders, with the victims of apartheid, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and in his role as archbishop. Central to all this is Tutu’s strong commitment to forgiveness and human identity, for without forgiveness our humanity and redemption is diminished.

This is not an easy book to read. It is very detailed and at times it is not clear whose spirituality and theology is being presented: Tutu’s or the author’s.

The book describes in detail Tutu’s spiritual life in terms of justice and reconciliation as core elements of his faith and ministry. It presents him as a man of courage and commitment, who speaks truth to power in the struggles of life. He has known discrimination yet tells the Christian narrative in a way that shines light on the darkness of human behaviour, emphasising the role that a victim can play in forgiveness and as reconciler towards those who abuse, exploit, dominate or exclude.

I commend the book not only because of Tutu, but for the credibility it gives to justice as a first principle of sharing God’s unconditional grace and love.

For more faith news, follow The Melbourne Anglican on Facebook, Twitter, or subscribe to our weekly emails.