Rhys Bezzant

11 February 2024

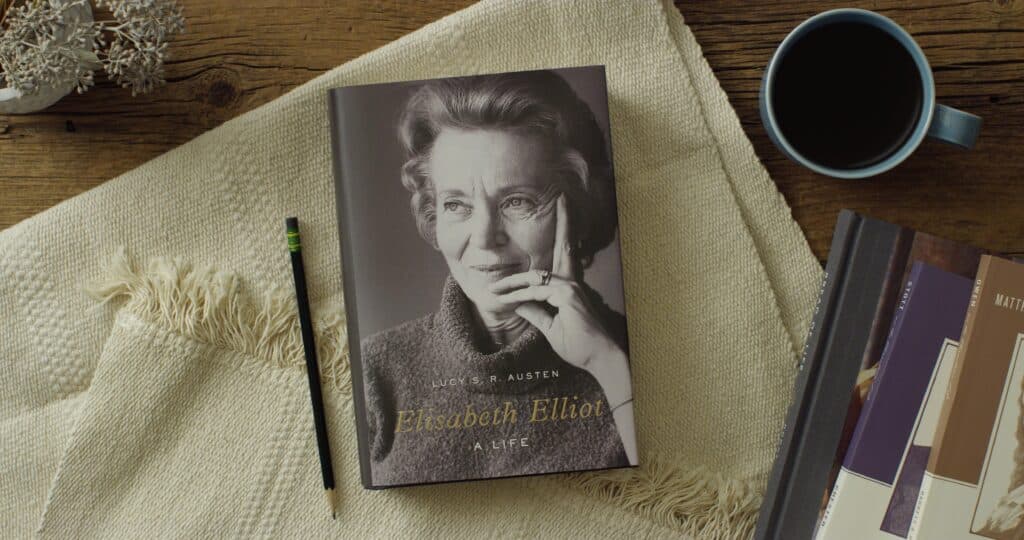

Lucy Austen, Elisabeth Elliot: A Life. Wheaton: Crossway, 2023.

At least she and I have this in common: Elisabeth Elliot (1926-2015), prolific author, linguist, American evangelical stateswoman, and wife of martyred husband Jim Elliot, loved reading Christian biographies. Of course, we should read commentaries on the Bible and books about theology. But something remarkable happens when we read the biographies of Christian leaders: we learn to make deep connections between our beliefs, our behaviour, and the broader culture around us. Christian biographies serve as a comprehensive workout for the soul. We need to read them more often.

This magnificent book by Lucy Austen achieves these things. We learn about an extraordinary individual who counted the cost in serving the Lord Jesus, whose ideas were sifted and reshaped during her life, and whose insights into global missions of the 20th century were inspirational for many. Reading so many Christian biographies herself, Elisabeth made herself open to challenges and growth.

Read more: A challenge to shallow reflection on place of singleness in the Christian tradition

A Marriage of Inconvenience

For many, the most we know about Elisabeth Elliot is that with her husband in the 1950s she tried to reach the Waorani people of Ecuador with the gospel, a tribe that had resisted contact with the outside world with both threats and acts of violence. Jim, with four other American missionaries, was killed in October 1953, leaving Elisabeth a widow with a 10-month-old daughter, Valerie. Elisabeth had in fact arrived in Ecuador unmarried. Jim had been writing sexually suggestive letters to her as they struggled to make sense of their calling, though publicly he preached a commitment to singleness for the sake of the Lord until he was quite sure that they should marry. (In their circles, being a single missionary was the highest calling of the Christian). Having been married for only two years and three months, Elisabeth stayed on in Ecuador after Jim’s death to support outreach among the Waorani, to offer her linguistic skills to other missions partners, and to write for the evangelical market. Some of her relationships with other missionaries were very difficult, a common story in missionary biographies.

Unresolved griefs and disappointments

Perhaps Elisabeth never really got over Jim’s death. In 1963, she decided to return to the United States for good to pursue a writing ministry, both fiction and non-fiction, and to speak at conventions and on campuses. Many of her articles and books reflected on her time in Ecuador. She never quite escaped its shadow. She married twice more, and on both occasions she surprised those around her by rushing into it. First in 1969 she married academic and Episcopalian Addison Leitch from a very different theological background, who died of cancer five years later. And then in 1977, Lars Gren, a Norwegian student at Gordon Conwell, who was nine years her younger, much more comfortable in social settings, and a great help to her ministry.

Read more: A clear case for freedom in God’s word – the Gender Revolution

Sadly, she was quick to discover how jealous and controlling both these husbands were. Her earlier fundamentalist background had permitted women to preach and teach in mixed gatherings – women preaching was a non-issue for fundamentalists in Elisabeth’s day – but as she grew older, her views became more conservative, and she found reasons to excuse her new husband’s abusive behaviour. Welcoming boarders into their home, they lived outside of Boston where Elisabeth taught at Gordon Conwell. Alongside teaching and speaking, she spent much of her time managing an increasingly voluminous correspondence as her advice was sought on missions, singleness, marriage, and issues in relationships. When she began to recognise symptoms of dementia, Lars helped to cover them up. She craved happiness and stability but rarely found contentment.

Power and Perseverance

It was a blessing therefore that Elisabeth was an introvert who could enjoy her own company, reminding us that leaders don’t necessarily have to seek a platform for validation. She took refuge in reading C.S. Lewis, George McDonald, David Brainerd, and especially Amy Carmichael (1867-1951). Carmichael was one of Elisabeth’s great role models, who as a single woman rescued young girls from temple prostitution in Bangalore, India, served the poor and challenged the powerful. Even when Elisabeth was living in the poorest of shelters in the Ecuadorian jungle, she read and wrote. Her heart for service was nurtured during her earliest formation in the Holiness movement, which taught paradoxically that power for ministry is to be found when we surrender our heart to the Lord. Her fundamentalist approach to reading the Bible gave her security in difficult days, yet she shed several fundamentalist skins as easy answers to life’s questions were scoured away.

Deep Movements of the Soul

One of the most intriguing elements of her life was how Elisabeth viewed guidance. Intensively, persistently, intimately, she sought the Lord and his individual will for her life. To anchor her decisions, she drew on images and words that she had recently encountered in the Scriptures, life circumstances that rerouted her, and the desire for a deep sense of peace. As Austen presents the ways that the Lord led her, I found the process incredibly exhausting, for Elisabeth was always second-guessing what the Lord would have her do that hour. With so much tragedy in her life, such an understanding of God’s guidance made her rethink if she had followed the Lord’s will after all. Her spirituality was both tender and tough.

Questions of Missiology

The training Elisabeth had in mission was barely adequate to the task she pursued. Of course, she was trained to expect hardship, which she experienced in spades. At the Prairie Bible College in Canada, there was no running water in the dormitory, so the women had to walk over to the barn to collect water in buckets. The men had it easier, their water was in the basement of the same building!

But when it came to transposing biblical ideas and stripping back North American cultural assumptions, there was a lot to learn. Her linguistic training did give her a head start. She was frustrated by colleagues who hadn’t benefitted from the study of language and couldn’t appreciate others’ worldviews. She told the story of a sermon preached to local Ecuadorian tribespeople, which was centred on the importance of addressing the Holy Spirit as “he,” and not “it,” even though in the local language everything in the creation was “he” or “she,” for it did not contain any pronouns for “it”! Her experience of self-propelled missionaries not attached to a mission society for training, support, and accountability is a sober tale.

Telling an honest story

In her own writing and speaking, Elisabeth Elliot was determined not to gloss over her negative experiences. She wanted to tell an honest story about how the Lord had led, and how his leading had resulted in great grief not just the glories of the Kingdom’s advance.

And indeed, Lucy Austen has taken up similar priorities in her own telling of Elisabeth’s story, recounting incidents of Elisabeth’s pigheadedness, failure to call out sin in others, inconsistencies in her theological system, and doubts about God’s providential care. She died in 2015 at the age of 88. The author searches out as many of her journals, letters, and public writings as are presently available to tell her story through her own eyes, not just as the widow of a famous martyr. And perhaps because of the honesty, this biography is also a supremely hopeful account of a woman’s life of dedicated service with powerful worldwide impact, despite the griefs and pains of her ministry and marriages, as she decided again and again to lean into the open arms of God for solace. Austen provides a detailed and compassionate account of a life well lived.

The Reverend Canon Dr Rhys Bezzant is senior lecturer in Church History and dean of the Anglican Institute at Ridley College Melbourne.