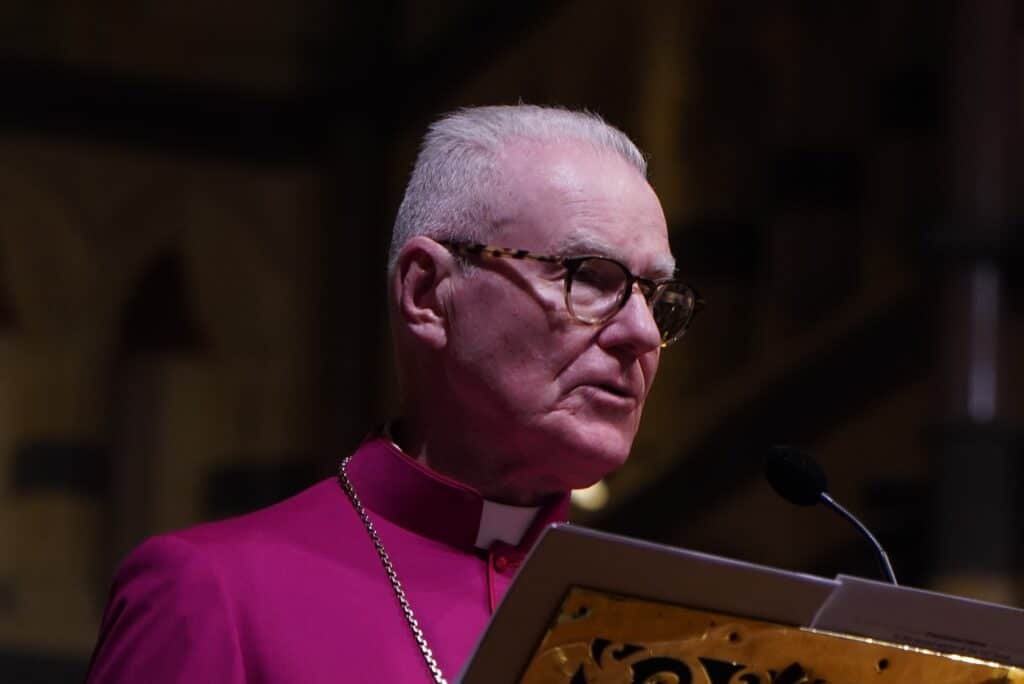

Archbishop Philip Freier

4 November 2024

When I hear people talking about a ‘secular society’ in contemporary times it often seems to be a shorthand for a set of values that restricts religious belief to the private sphere, something that may be personally held but best kept out of public view. I think that this an incorrect interpretation.

A secular society is most accurately one that gives no unique preference to any particular set of religious beliefs but creates the freedom for all to be expressed. The operation of the State and the freedom to practice religious belief coexist without coercion.

Even though it is a related word, secularism is however different, as it carries with it a set of beliefs about human society best thriving where there is an absence of religion.

Secularism is inclined to push religion into a private realm. Under this vision religious ideas become less meaningful and the traditions that uphold them become more marginal to the society.

Such a secularism inclines towards a belief system that human society is entirely capable of being its best without reference to the divine or any transcendent principle. I think that it is because of this that societies like ours struggle to make sense of evil and even human failure.

We become accustomed to hearing structural reasons for human failure rather than attributing it to moral choice. Morality under this schema is corporatised into the things that are controlled by Government rather than being recognised as inherent to human virtue.

Read more: A timely text as we face political turmoil: Jesus and the Powers

In 2015, I was pleased to be involved in hosting the English political theorist Lord Maurice Glasman to Melbourne in my role, at the time, as chair of the Brotherhood of St Laurence.

Glasman delivered the Brotherhood’s 2015 Sambell Oration on the significance and challenge of pursuing the common good. From the perspective of his English experience, Glasman spoke of how he greatly admired the Church of England for its embodiment and preservation of the common good tradition in the modern world.

In his experience of working with and learning from the poor in their diversity and deep needs, he noted the significance of vocation and virtue. These two principles have ongoing relevance in building up human society. They are the source of vision and strength in a time of turmoil and polarisation. Otherwise, competition and criticism too readily breakdown what otherwise might be held in common.

Glasman noted that the common good tradition emphasises the “importance of family, place and work and the threat posed to what they loved by an exploiting market and an uncaring state.”

As recently as June this year, Glasman speaking to another Christian audience in England said, “Have confidence in your faith. Don’t despair and live your faith in public.” A different narrative indeed to that offered to us from a secularist ideology.

Community groups, Glasman says, can best maintain their vocation where they are neither an instrument of the state nor a private enterprise. The former isolated from relationships and the latter dominated by KPIs, well paid executives and shareholders.

The world needs the transforming message of the Gospel, let’s make sure that no ideology keeps us from speaking its truth.

For more faith news, follow The Melbourne Anglican on Facebook, Instagram, or subscribe to our weekly emails.