Dr Toh reflects on her own success-orientated life and her observations of the wider world

By Stephen Cauchi

21 September 2021

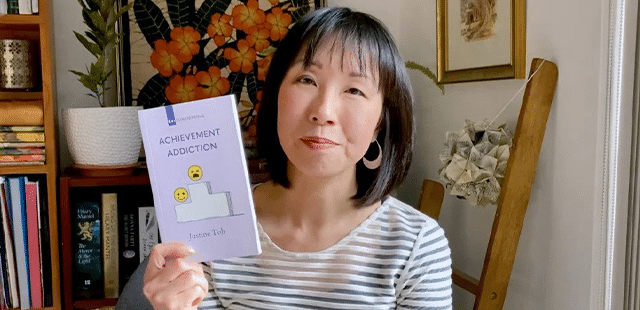

We live in a world that worships achievement, but Justine Toh, the author of the just-released Achievement Addiction, has witnessed the downside: a stunted life, poor self-esteem, and spiritual harm.

Dr Toh, a senior fellow at the Centre for Public Christianity, wrote the book partly as a memoir of her own success-orientated life and partly as an observation of the wider world.

“We live in a world obsessed with merit and achievement,” writes Dr Toh, who lives in Sydney. “We’re collectively addicted to achievement — and we can’t get enough of it. Our culture worships hard-won success above almost everything.”

However, if we internalise this attitude, she says, we need to work hard to maintain our value as people and workers.

“Achievement addiction may not be fatal,” she concedes, “but it’s no way to live.”

Dr Toh counts herself an expert in achievement addiction, given her life background as someone who was “tiger-parented” (strongly encouraged by her parents to achieve success.)

For her parents – Chinese migrants from Malaysia – sucesss meant studying hard and being academically successful.

“For my parents it was really important for my sister and I to go to a selective high school and they were prepared to spend money for coaching for us in order to get a good mark in the HSC,” she told TMA.

Her sister got into a selective high school; unfortunately she didn’t.

As a result, her high-schooling passed in a “fog of shame”. “My adolescent self was frantically striving because I believed that the quality of my work was directly tied to my worth,” she said. “It was a real inferiority complex.

“Even if I topped my class at my public high school, I felt like I would be only halfway in the pack at a selective school.”

Dr Toh said she loved her tiger parents dearly, and appreciated the work ethic they gave her, “but it did sometimes feel as though that my acceptance in this family was contingent on doing well in my studies.”

Achievement, says Dr Toh, means very different things for different people: a high paid, fulfilling job; a good house in a good suburb; a model family.

“For some people it’s a corner office, for others it’s an instagram account with a million followers. For some it’s a big salary, for some it’s having the perfect family.” For her, it’s high marks, “achievements that would look good on a resume.”

But while the idea of achievement may differ, the negative result is the same: “a stunted vision of what life is truly about.”

“All of us are on some kind of achievement journey. We just do it in different ways. Everyone is trying to do this is some way. It just doesn’t look like achievement always”.

A key sign of an achievement addict, she said, is when “their world falls apart” after they lose their job, get a poor grade, blow the game, or just receive critical feedback.

But being “too over the moon” when they achieved something was also a sign. She recalled writing an article she was so pleased with she began “stumbling around my workplace like I was drunk”.

A key focus of the book is the spiritual cost of an overemphasis on achievement. “For many people, definitely for me, it’s a way of securing your significance in life and knowing that you’re ok.

“I really wanted to start a conversation around what we expect our achievements to do for us spiritually. If we are building up our identity in our achievements then that is not something you can sustain all through life.”

Retired Olympic swimmer Stephanie Rice, for example, suffered a breakdown during the Tokyo Olympics while reflecting on her past career.

“She talked about how the adjustment was incredibly difficult and for that reason the Olympics has really mixed emotions for her.

“All of us are like that a bit. What happens if we retire or get sick? “Where is your identity then?”

Dr Toh cited the 1998 book The Call by British Anglican Os Guiness as a guide to the emphasis that God expects us to put on achievement.

Thinking of your life in terms of calling “completely changes the game of achievement,” said Dr Toh.

Achievement is “labouring to secure your own meaning in life, your own significance”. The attitude of calling , by contrast, is “I’ve been given these capacities and with God’s help I’m going to grow more fully into the person he is calling me to be.”

Os Guiness, says Dr Toh, writes of how we actually have two callings. “There’s the initial call in to God, to be known and loved by him and to know and love him; and the second call is the opportunity to serve God and the wider community with the gifts that he has given us.”

The key difference then, between achievement and a calling is that with a calling “you’re not working for yourself, you’re working for God”.

Not is there an issue of self-esteem involved, as there might be with achievement. “You’re not doing it to make yourself worthy for God. He’s already secured your worth, your infinite worth, because he loves you, regardless of your achievements. At the same time, he is calling you to particular kinds of work, and this is a wonderful opportunity for service.”

What a person with calling feels, she says, is “humility” and “peace”: “completely the opposite of the achievement addict and the arrogance that they might feel at having worked so hard and achieved their goals.”

Having said that, maintaining a calling mindset is “really tough”.

“If I find that my prayer life is constantly consumed by my own agenda, that’s probably an indication that I need to reconsider that.”

Another way foster a calling mindset is to maintain a sense of gratitude.

“Try to remember and tabulate the many great things that we can be grateful for,” said Dr Toh.

“I was born in a country, I was born in a century that enabled me, just an ordinary person, not born to riches or royalty, to be able to make a go at my life and to develop my gifts. That is an incredibly privileged experience to have in terms of growing up in the west today rather than in a developing country.”

Dr Toh said she had not completely cured her achivement addiction, which she said was “ongoing”.

“In an ultimate sense I’ve been cured of my achievement addiction. I know full-well that my ultimate worth does not lie in the work of my hands. I know that it lies in the gracious gift of God who has loved me in spite of what I have or have not achieved.

“But in a day-to-day sense I think it’s a constant struggle for me to remember that.”

Achievement Addiction is available for $7.99 at Koorong.