By Chris Shearer

7 December 2022

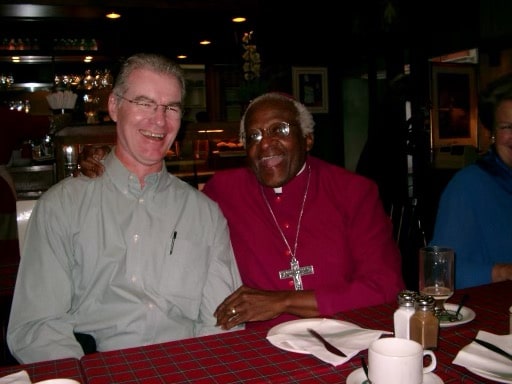

Colin Griffiths, Retired Priest in the Diocese of Ballarat, Society of the Sacred Mission

It was December 1982 when Colin Griffiths arrived in Johannesburg for a course on Lesotho’s local language. The young Australian priest had recently begun a two-year stint in Lesotho, what he would later consider something of a second curacy. He was in apartheid South Africa, staying with a religious order that was very close to the then General-Secretary of the South African Council of Churches, man whose anti-apartheid activism had already made a name for him both at home and abroad. This was of course, Desmond Tutu.

“One Sunday I was taken out to Soweto where he was ministering,” Mr Griffiths recalled. “He greeted me very warmly: he was very warm.”

For years the South African government had tried to paint Tutu as a communist sympathiser. Many white South Africans were afraid of him, and even several anti-apartheid whites had publicly criticised his rhetoric, including former Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town Bill Burnett.

But Mr Griffiths saw none of that on that Sunday in Soweto. What he saw was a man who cared deeply about his people and his faith, a man of humility, a man who wanted to make a young Australian priest feel welcome.

“I was in Soweto, a huge African township, so I wasn’t in my comfort zone,” Mr Griffiths said. “He went out of his way to make me feel at home,”

Tutu invited him back to his home for lunch along with a number of local clergy. Mr Griffiths remembered that there the group talked affably and joked, but also despaired over what they saw as their lack of impact against apartheid. They were non-violent, and the state was so entrenched that it seemed unconquerable to them on that Sunday in December 1982. But even so, Mr Griffiths found himself impressed by the Tutu’s commitment and humility.

“He gave me a lot of hope that they would eventually succeed,” he said. “Next minute he’s made Bishop of Johannesburg. Next minute Archbishop of Cape Town. Next minute Nelson Mandela was released.”

It would be around twenty years before the two men met again.

Apartheid was over, South Africa was a democracy, and Archbishop Desmond Tutu was wrapping up his work with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Mr Griffiths didn’t ask him if he remembered the post-service lunch in Soweto all those years ago. Too many faces and too many terrible and beautiful moments had passed since then. But Mr Griffiths could see the man still had the same vitality and humility as he’d had on that day he had greeted the young Australian priest so warmly.

“He was just dedicated to peace and justice, to the freedom of his people. There was no ego.”

Father Hugh Kempster, School Chaplain and former Vicar of St Peter’s Eastern Hill

Hugh Kempster had only recently found what he called an adult Christian faith. It was the mid-1980s and he was in the United Kingdom studying electronic engineering. One day a couple of friends told him to come along to the “Desmond Tutu rally”. Dr Kempster said he didn’t really know a great deal about Tutu at the time, but thought he should go take a look anyway.

“I went along to the rally and it was just incredible,” he said. “It was a bit like the Pope arriving in Cardiff!”

Throngs of people had gathered in the outdoor stadium in an almost electric atmosphere. And at the centre of it all was one man.

“There were thousands and thousands of people,” Dr Kempster remembered. “This small figure away in the distance was booming from the speakers with incredible energy.”

Although the specifics of what he said that day have been lost in his memory, Desmond Tutu’s words inspired the young Dr Kempster. Tutu’s commanding oratory educated him on the issues of apartheid, but also helped ignite a passion inside Dr Kempster that would guide his trajectory over the next four decades.

“Here was a Christian man, a bishop, who was at the forefront of a major social justice issue in the world, and gathered this great crowd of people. That really underlined for me, who had just become a Christian as a young adult, that being Christian is not just about Sunday,” he said.

“What happens in our worship is the food that provides the voice, the action, the engagement with what really matters in the world. Bringing about change where there is injustice, where things are wrong at a societal level. Getting involved beyond just the individual Christian journey.

“It definitely helped to shape who I have become as a Christian and then a bit later as a priest.”

Anglican Archbishop of Melbourne Philip Freier

Dr Freier had the good fortune of meeting Tutu on several occasions in both Lesotho and South Africa.

“He was a remarkable person, but also unremarkable, and I think that is the remarkable thing about him,” he told The Melbourne Anglican.

“When you met him, he didn’t seem like a high-powered guy, you know, ‘Stand aside, I’m coming through’. Just a pretty normal, humble sort of guy in all aspects of his life.

“He had consistently tried to apply the things he had learnt from his spirituality and his formation, and apply these principles as he’d come to them without fear or favour. In that respect I don’t think he was planning to be a politically influential person, but in the different roles he had, in the society that he lived in, he was saying some pretty plain and straightforward things when everyone else thought they were unusual and exceptional.”

More than just a humble man, Dr Freier remembered Tutu as a deeply joyful and caring one too.

“When you met him, you didn’t feel things were about him,” he said. “They were more about the people he was with.”

Dr Freier, who was Bishop of the Northern Territory the first time they met, remembered Tutu dancing and “really getting into” one of the traditionally lively greetings-of-the-peace that happen during services in Lesotho. Dr Freier recalled him later asking about how one of his clergy was doing. He had never met the man, but had received a copy of the Anglican Board of Mission Australia prayer diary and had been praying for him.

“He had this lovely kind concern for people,” Dr Freier said.

During that same visit, he remembered Tutu telling a story about former Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney who had stepped into an elevator with a woman who turned to him and said “you poor thing you look just like Brian Mulroney!” Embarrassed, Mulroney had said nothing and got off at the next stop, but Tutu thought the punchline was an absolute hoot.

“I think he was saying this to me, who was new in the business of being a bishop, that you’ve got to find that balance of what others perceive of you and what you actually are inside of you,” Dr Freier said.

“For someone with such an international reputation he was a humble and approachable person. I’m not surprised people have reacted to his death with such expressions of appreciation as well as grief.”

If you have any stories about encounters with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, TMA would like to hear them. Please contact cshearer@melbourneanglican.org.au.