Stephen Cauchi

31 March 2022

The life of a seafarer has always been difficult but during the COVID-19 pandemic it has been close to unbearable.

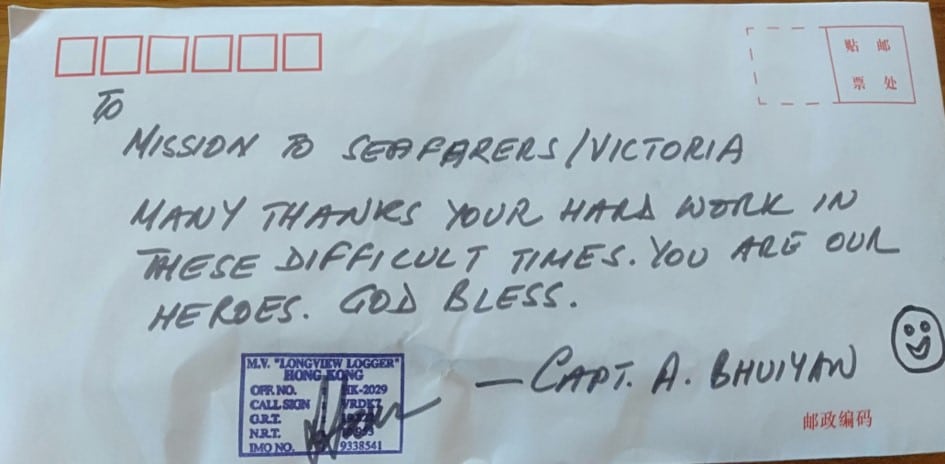

It’s meant the Anglican Mission to Seafarers has been flat out caring for ship crews who now don’t even have access to the meagre eight hours shore leave they once enjoyed.

Nor do they have the option of signing off from the ship, so they can return home by air.

The Flinders Street-based mission’s head chaplain the Reverend Onofre Punay said seafarer’s suffering was a recognised humanitarian crisis.

“There are lots of issues during the pandemic – seafarers that weren’t even allowed to sign off from the ship because of the unavailability of flights during the lockdown.

“It’s not unusual to hear of seafarers being on board for two years.

“It’s really a crisis. They’re forced to extend their contract because there’s no flights available.”

Mission to Seafarers operates in 200 ports throughout the world, with other centres in Victoria at Geelong, Hastings and Portland. The Catholic Church operates the similar Stella Maris Seafarer’s Centre in Little Collins Street.

Mr Punay said that pre-COVID Flinders Street centre would have 80 to 100 people a day, or over 30,000 a year, with similar numbers at Stella Maris.

Seafaring to overseas destinations might exciting, but the reality is seafarers only get eight hours a day in the cities they visit – if they’re allowed off the ship at all.

They must sleep onboard, and work loading and unloading cargo. Usually the ship has just one day in the port before it leaves.

“[Seafarers] work for four hours, and then go off for eight hours, and then they go back to work again,” Mr Punay said.

“They’re usually in a hurry. The main service that we do is transport from the port to our centre and from the centre to the port.”

Most seafarers spend 4am to 8am working, then 8am to 4pm on any shore leave. Mr Punay said some ships had a multi-day stopover in port where crews could go out every day, but most did not.

This assumes of course that seafarers are allowed off the boat at all. Mr Punay said shore leave was like a lottery.

Pre-COVID about 200,000 to 400,000 seafarers came to the Port of Melbourne every year, but only 30,000 would visit the mission’s centre.

Shore leave had to be approved by the captain, while the seafarers had a strict time limit out of the port, monitored by security guards.

“You need to be very, very lucky as a seafarer to be able to go out in pre-COVID times because they are still working. Sometimes they are tired. They’ve probably been stressed with the weather or while coming in here, so they need to have a rest,” Mr Punay said.

Onboard, life is isolating. Mr Punay said few ships had wifi, and email was the most common form of communication.

To help address this, the mission offers seafarers the purchase of SIM cards from its centres.

Despite the strictures, standards for living and working conditions on ships are regulated when the vessel enters Australian waters, under the Maritime Labour Convention implemented by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority.

Part of the job of the Mission is to advocate for the welfare and living conditions of the seafarers.

For instance, if seafarers work and haven’t been paid properly the mission must report that to the AMSA, which has the power to inspect and even detain ships.

Mr Punay said abuse of seafarers by shipping companies still took place, but the industry had learned a lesson about what to expect when they came to Australia.

He said the AMSA was – to its credit – very strict about the regulations and documentation shipping companies must adhere to.

When seafarers are allowed to come onshore, they use the Mission’s Flinders Street headquarters as their base to go out into the city, get information, and change money.

Mr Punay said some even went directly to the chapel to pray before they went out, or before they went back to the ship.

In terms of activities, Mr Punay said shopping and eating were very popular with the visiting seafarers.

But he said since March 2020 seafarers had not been able to take any shore leave at all, and it was not certain when this would resume.

“Because of COVID, no-one wants to make a decision at this time in terms of departments of the government,” Mr Punay said.

“Then there’s also the port and there’s also the shipping company, who don’t want their seafarers going up and about in COVID-infested Melbourne.”

The isolation means Mission to Seafarers must deal with not only the mental health of seafarers locked in the port, but also their spiritual and physical needs.

Chaplains and other support staff are not able to make in-person visits to ships, but can “visit” seafarers online.

Although the seafarers’ centres are empty and there’s no physical meeting, Mr Punay said he has been busier than ever during the pandemic.

For him, the situation means he can spend all day replying to emails and inquiries, and sending messages to ships coming into the port.

Mr Punay said mission staff were also able to buy supplies and drop them off at the port without interacting with the seafarers, which fortunately they had been able to keep doing despite restrictions.

In 2021, the Flinders Street centre purchased $500,000 worth of goods requested by seafarers, visiting supermarkets, electronic stores and chemists. Grocery items, SIM cards, internet cards and were among the popular items.

The mission also donates care packages containing dental and shaving kits, books, puzzles, reading material, and knitted clothing from volunteers, and prize packs to encourage seafarers to take part in recreational games onboard the ships.

“They only have each other to lean on for support so we’re trying to strengthen their camaraderie or team spirit on board. We try to encourage them to have some sort of recreational games,” Mr Punay said.

“Some ships are very glad about [the prize packs] and they keep sending photos of winners of the games that they’re doing.”

Catering for the spiritual needs of seafarers is challenging given their wide background.

The Philippines is the most common place of origin for the seafarers, but many are also Indian, Chinese, or from Europe or other Asian countries.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the mission’s chaplaincy team’s main activity was visiting ships. It was especially important because not all of the seafarers in port were allowed onshore

Sometimes they talked about spiritual matters, at other it could be about the working conditions on the ship.

“If there is some sort of trauma that happened on board, we offer counselling and sometimes aspect of spiritual care for those who need it,” Mr Punay said.

“Sometimes we end up praying for them. Sometimes they do require some sort of service onboard – like a Eucharist.”

Any services on board the boat are non-denominational, as the most common backgrounds for crew were Catholic or Orthodox.

Mr Punay said mission workers would often offer to pray for crew-members, and were often taken up on that.