Dorothy Lee

28 October 2023

We are very confident in speaking about the Bible and holding up a single book, nicely bound together, containing 27 books that we call “New Testament” and 39 (or 46) books we call “Old Testament” or “Hebrew Scriptures”. We are equally confident to see those ancient books and their authors as connected in a direct line to ourselves. So we can refer to Isaiah or Jeremiah speaking directly to us, or Paul or the gospel writers.

Read more: Bible being used to subjugate Indigenous Australians: Pattel-Gray

Those attitudes are fine as far as they go. But we need to be aware that they are, at best, a simplification and in some cases even a distortion of the history of the Bible and how it has come down to us. We need to be aware of these issues so we can truly understand how the Bible can be God’s word in human words. Here are some of the factors:

- Not until the fourth century CE do we have a copy of an actual “Bible”: a single book containing all the books we know in the Bible. There are two of these and they are written on parchment as codices (i.e. books) rather than papyrus scrolls. One is called Codex Vaticanus and the other Codex Sinaiticus, both named either for their current origin or location. They are similar to each other and contain most of the Bible. Codex Sinaiticus is unique in that from the fourth to the 12th centuries thousands of corrections were made in several different hands. Sinaiticus also contains two added books that, in the end, did not make it into the canon.

- Both codices are written in capital letters without spacing between the words and almost no punctuation. They have no chapters or verses as these were added later: chapters in the 13th century and verses in the 16th. They were written completely in Greek, including the Old Testament, which was based on the translation from Hebrew in the third century BCE. This translation, called the “Septuagint”, was used by Jewish people outside Palestine (particularly Alexandria) for whom Greek was their first language. The Septuagint, which includes the Apocrypha, was the Bible of the New Testament church.

- Our two codices were not used in translating the Bible into English until the 19th century. The King James Bible was based on a later manuscript tradition that we now consider somewhat corrupted by scribal changes. For example, the KJV includes the story of the woman caught in adultery (John 7:53–8:11) and the longer ending of Mark’s Gospel (Mark 16:9-20), neither of which is found in the earliest witness, including Sinaiticus and Vaticanus.

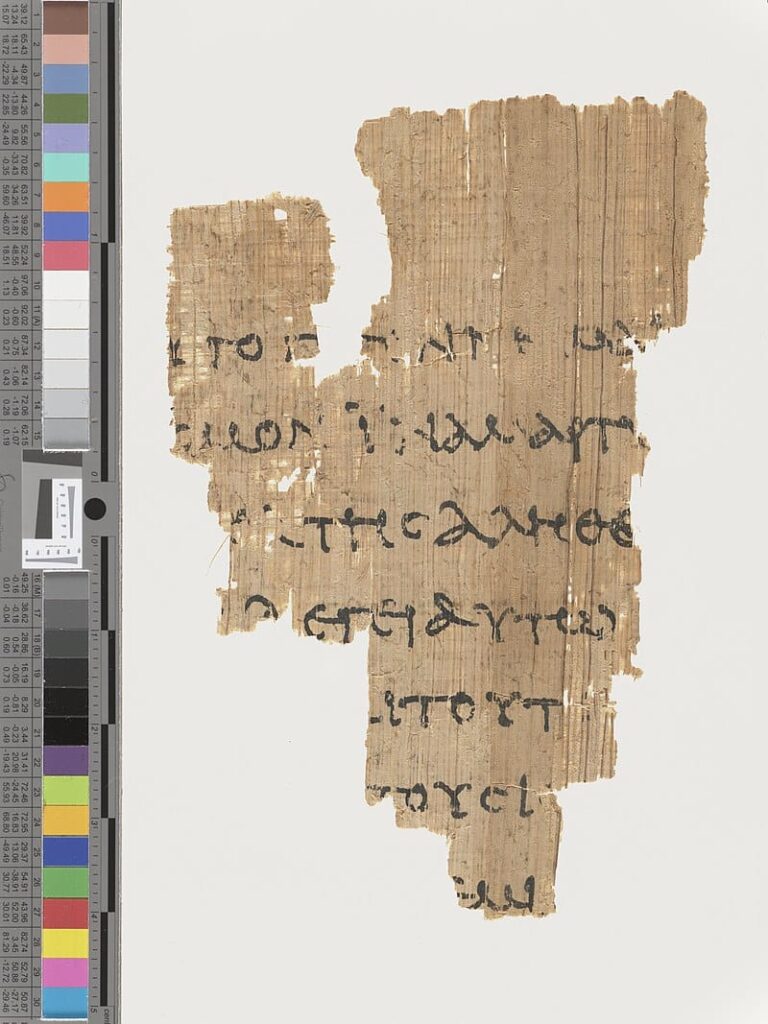

- In addition to these two great codices, there are other manuscripts (from a later period) as well as a growing number of papyrus fragments from even earlier. The oldest of these for the New Testament is P52 which contains a small portion of John’s Gospel, dated to the second century CE. At the turn of the 20th century, a group of papyrus fragments was found in an ancient rubbish tip in Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, which has 52 of the 127 fragments of the New Testament we now have, dating from the second to the fourth centuries CE. Some of this collection is still being released.

- The biblical scholars who have put together our Bible, and who continue to do so in the light of new discoveries, are called “textual critics”. They have to examine various manuscripts to determine what might have been the original form of any biblical book. This branch of biblical studies is on the verge of a revolution, however, as more and more texts are being computerised. Textual critics will soon have all available texts online and can work out more accurately their genealogical relationships to each other. Note that it is texts that they study and not just manuscripts, as the same manuscript with several biblical books might have been copied from a variety of other manuscripts.

- Two factors complicate things here. Firstly, we do not know for certain that there is such a thing as an “autographed” copy of any biblical book. The New Testament texts, particularly the gospels, originated in written form but were probably communicated public performance. Was there only a single version of Mark’s Gospel that circulated? Was Q (the likely source of the sayings in common between Matthew and Luke) originally an oral source? Is it possible that John’s Gospel originated two forms, a longer and a shorter version? The ancient world may have produced many literary works but it was largely an oral culture; people had prodigious memories and clear methods of memorising.

- Secondly, textual critics need to make their decisions on internal as well as external grounds. That means they have to study the texts themselves, trying to work their way back as close as possible to the initial form of the text. But they also have to study internal evidence: the style, the context, the theology of each biblical writer. So, for example, on both grounds – texts within manuscripts and Paul’s own theology – they conclude that 1 Corinthians 13:3 says “boast” rather than “burn”: “if I give up my body that I may boast”, and not as in the KJV, “If I give up my body to be burned.” It would also seem that Mark’s Gospel commences with the words, “The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, son of God” (Mark 1:1), even though some manuscripts (and some commentators) omit the words “son of God”. Here textual critics work with exegetes to determine the best reading. In some cases, a decision is unclear. Does Jesus say, “I will draw all things to myself” or “I will draw all people to myself” in John 12:34? There is only the difference of one letter in the Greek. Manuscript evidence, textual critics, exegetes are divided on this issue. New evidence may arise to resolve the issue.

What are the implications of all these factors? Above all, it means we need to look forward to new editions of our English translations that will take into account new discoveries, particularly the computerising of ancient texts and manuscripts. We need not be afraid of new technology. The earliest Christians embraced the book form and abandoned the papyrus roll very early on, ahead of their culture, probably because it allowed them to include a number of texts in the one volume: e.g. the letters of Paul or the four gospels.

Read more: Bible translation turns a new leaf for 21st century

It also means that we need to regard the biblical texts not just as direct communication to us from God, but also as historical documents which have come down to use through the centuries. We have received them thanks to the painstaking work of countless scribes, female as well as male, who copied, considered and corrected manuscripts because of the love and reverence they had for the Bible as the prophetic and apostolic witness to the Word, Jesus Christ. We are united with them as we read, study, proclaim and live out the sacred text.

We in the West should be particularly grateful to the scribes who translated the Bible into Latin and passed it down through the centuries in that language, before the original Greek came to the fore. Indeed, we should be grateful to all translators, including Bishop Thomas in the seventh century who translated the New Testament so literally into Syriac that we can construct something of the original Greek text!

We have the Bible today because of loving and hard labour well before the printing press: copying by hand, correcting, translating, separating words, organising paragraphs, adding chapters and verses. We should be aware that the Bible comes to us inspired not only by God but “inspired” also by those who loved and copied and translated it over many generations.

The Reverend Professor Dorothy A. Lee is Stewart Professor of New Testament at Trinity College, University of Divinity.

For more faith news, follow The Melbourne Anglican on Facebook, Instagram, or subscribe to our weekly emails.